I watched the weather radar from home, frustrated by doctor’s appointments and other domestic obligations that would keep me away from the East Mojave during one of the first thunderstorm events of what had been so far a “non-soon” Monsoon season (storms and rain failed to materialize across most of the southwest during the summer “rainy” season). I would be there soon. It was August 15, 2020. You might think that mid-August is no time to enter the desert, especially solo, but the high elevation regions of the Mojave National Preserve (MNP) sustain mild-enough temperatures (dependent upon one’s comfort levels) through most of the summer to make life possible here. Even better, the higher elevations of MNP are dressed in beautiful juniper and Joshua Tree woodlands, offering plenty of shade, rich and diverse plant life, and abundant wildlife.

Appointments would keep me in town through the afternoon of August 19, and I would then depart for the Preserve to hopefully meet the next arrival of monsoonal moisture. On the afternoon of August 16, my stomach sank when I learned of the fire through a Facebook group. It began following a series of dry lightning strikes at 3:51pm on August 15 and was already burning quickly through Joshua tree woodland with unstable weather and high winds exacerbating the flames. In just over 24 hours the fire had taken 20,000 acres.

From home, sick to my stomach over the fire, I kept a close watch on incident reports and social media and quietly wept inside. Early on the 20th I received word that road closures had been lifted and I quickly departed for the Preserve.

It was named the Dome Fire (fire map) for its origin on the geologically unique Cima Dome, a symmetrical ten mile wide granitic bulge in Earth’s crust which is revealed in nearly perfectly concentric rings on the USGS topographical map. The fire had begun on the south and west perimeter of the dome and pushed east and northeast, directly over Cima Dome and Teutonia Peak, before roaring into the Ivanpah Mountains. Aided by improved atmospheric conditions, hundreds of firefighters, and air drops of water and Phos-Chek, the fire was mostly contained and extinguished by August 19. But not before the fire had consumed more than 43,000 acres of beautiful Joshua tree desert woodlands. In less than four days nearly the entirety of the Joshua tree forest on Cima Dome had burned.

As I headed southbound on Cima Road, I could see clearly the burn scar on the dome from more than ten miles away, but it was a smoky day with poor visibility – hundreds of fires were burning throughout California and the west – and it was difficult to make out any details from this distance. Within just a few miles of the northern fire line the true scale of the fire became evident. I knew exactly how many acres had been declared burned but had not yet converted it to a relatable number: before me was 68 square miles of burned Joshua tree woodland. Not just any Joshua trees, but the largest and densest Joshua tree forest we know (they are found only in California, Nevada, Arizona, and Utah). I left the pavement at the northern fire line and in utter disbelief headed off onto a dirt road into the thick of it. I stopped and climbed atop my truck to survey the damage and what I saw appeared to be little more than a fire-blackened wasteland. All I could do was cry.

It is important to understand why I would write this story or why I would cry over Joshua trees. This place is dear to me. I currently serve on the Board of Directors for the Mojave National Preserve Conservancy and for more than twenty years I have been exploring and adventuring in the Preserve and this was one of its most special gems. Plants, animals, and ecosystems are my interests and subjects. I can’t tell you much about contemporary culture, sports, or cinema but I can name plants by their binomial names and birds by their songs. In 2011, I was Artist in Residence at the Preserve and I concluded my residency with an exhibition at the Preserve’s Kelso Depot showing – that’s right – my Joshua tree collection. Sixteen years ago I rescued my dog, Mojave, from the Mojave desert just eighteen miles west of the summit of the Dome. We spent a lot of time here together, reveling in its extraordinary beauty, climbing the mountains that ring this beautiful valley, and studying its starry skies. She crossed the Rainbow Bridge just two and a half years ago and this fire reopened a bad wound.

Unlike desolate alkaline basins which can feel uninviting and inhospitable, this is the most inviting portion of the desert, where Joshua trees and their shrub communities offer abundant welcoming shade and respite from a weary sun. This was the place that defied the typical expectations of the unwitting; where healthy jackrabbits, cottontail rabbits, and antelope ground squirrels would flit between shrubs or sun themselves in the open; where choruses of coyotes would yip and howl by night; and where even a committed bird watcher would find delight in the resident Gambel’s Quail, wrens, phainopeplas, mourning doves, mockingbirds, and black-throated sparrows – a comforting place of diversity, abundance, and tranquility.

For three days I walked through a charred landscape, revisiting familiar places and trees, only now dramatically altered by the fire – much of it a high intensity burn, with everything lying in its path completely consumed. The ground was scrubbed bare, left only with the black stains of complete combustion or white piles of ash. The wildfire had lapped at and barreled over large rock formations, reaching into crevices and caves and consuming everything: grasses, shrubs, trees, cactus, moss, lichen, even rat middens. Life seemed completely absent. These were incredibly difficult scenes to witness and process. Yet I felt I had an obligation to be here, to mourn and to grieve the tremendous loss of vegetal and animal life and an absolute transformation of a landscape I love, and to try to use my voice, my photographs, as a means to hopefully spark dialogues as to how to help better protect these trees and this landscape from the future threats they face.

Many California ecosystems and plants are fire-adapted (or dependent) and fire can be highly beneficial to them, yet it’s deadly for non-adapted desert ecosystems like Cima Dome. Where a lightning strike might have formerly taken out one tree and its surrounding brush, the extensive destruction of the Dome Fire is the result of several factors, most significant being a changing climate. For those of us who spend a significant amount of time out of doors, drastic changes in the natural world present abundant signs of impending climate change disasters. California fires have become increasingly large and destructive and will only continue in this direction under the current climate regime – at least until humans find themselves willing to accept and tackle our most existential threat.

I’m showing only a limited selection of photographs here. You can find here a growing gallery of my photographs from the Dome Fire aftermath; I hope you will return to the gallery for updates.

The Conservancy will be discussing with the National Park Service any possibilities for our involvement with rehabilitating the land. If you would like to be notified of ongoing efforts and potential volunteer opportunities, please consider following MNPC on its website or on Facebook.

Resources:

TAKE ACTION: Reduce Your Carbon Footprint (the reader may be confronted with inconvenient truths)

TAKE ACTION: Iconic Joshua Trees Need Your Help Right Now

INCIWEB Incident Reports and Maps

What the Fire Took Chris Clarke by Chris Clarke

L.A. Times: Mojave Desert fire in August destroyed the heart of a beloved Joshua tree forest

Dome Fire’s destruction of Joshua trees reminds us of climate change’s carnage

You are visiting the blog of landscape photographer Michael E. Gordon. For additional photos and information, please visit his website or follow him on Facebook and Instagram.

I was immediately drawn to the delicate but elaborate etchings on one particular fruit – I honed in. Space and space exploration has been on my mind a lot lately. I spend many nights each year staring deeply into it and sleeping under it and NASA’s InSight Lander touched down on Mars just thirteen days after this photograph. I like to use space and time metaphors in my images and titles. The etchings reminded me of planetary surfaces similar to Jupiter or the Moon. This became the metaphor that I forced into my approach.

I was immediately drawn to the delicate but elaborate etchings on one particular fruit – I honed in. Space and space exploration has been on my mind a lot lately. I spend many nights each year staring deeply into it and sleeping under it and NASA’s InSight Lander touched down on Mars just thirteen days after this photograph. I like to use space and time metaphors in my images and titles. The etchings reminded me of planetary surfaces similar to Jupiter or the Moon. This became the metaphor that I forced into my approach.

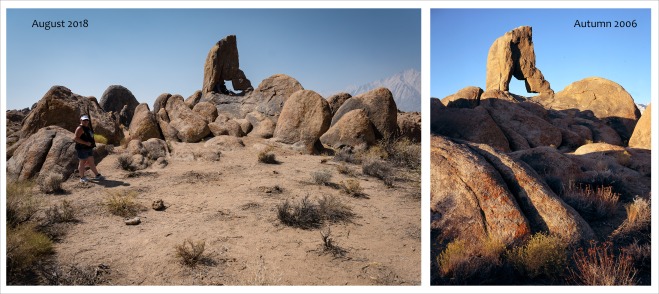

I took my sister and family to a lesser known arch in the Hills (but still popular with night photographers) and was dismayed by what we walked into: it looked obliterated by grazing cattle (there are no grazing cattle here). Although from different angles, perspectives, and focal lengths, a comparison of the two images will reveal missing, damaged, or dead plants. And I am dumbfounded by this. The other side of this arch does not look like this; it’s not the preferred angle for photographers. This is not from drought, fire, or cattle, and this is not a dense landscape – the shrubs could have been very easily avoided or worked around. Instead, the land before this arch has now become a micro-wasteland.

I took my sister and family to a lesser known arch in the Hills (but still popular with night photographers) and was dismayed by what we walked into: it looked obliterated by grazing cattle (there are no grazing cattle here). Although from different angles, perspectives, and focal lengths, a comparison of the two images will reveal missing, damaged, or dead plants. And I am dumbfounded by this. The other side of this arch does not look like this; it’s not the preferred angle for photographers. This is not from drought, fire, or cattle, and this is not a dense landscape – the shrubs could have been very easily avoided or worked around. Instead, the land before this arch has now become a micro-wasteland.